ELMterm, CornucopiaStreams, and the joy of clean automotive telemetry

Back in 2016 I fell deep into the rabbit hole of automotive diagnostics. What started as “let me decode one CAN frame” quickly became a multi‑year tour of every adapter I could get my hands on: ELM327 clones, genuine STN units, Bluetooth dongles, USB‑serial cables, Wi‑Fi gateways, even a few early BLE UART experiments. Each promised to be the answer, yet every session ended with the same friction—flaky transports, unreadable hex dumps, and notebooks full of copy‑pasted traces. Eventually I built my own hardware so I could trust the bits on the wire, but I still lacked a terminal that respected the data I was seeing. That is why ELMterm exists.

Why another terminal?

Classic tooling (nc, telnet, minicom, picocom, …) treats adapters like anonymous byte pipes. That’s fine for a quick sanity check, but terrible when you’re juggling OBD‑II, UDS, ISO‑TP, and vendor quirks day in, day out. ELMterm knows the automotive domain: it annotates AT/ST commands, explains diagnostic modes, reassembles ISO‑TP bursts, and highlights negative responses, ASCII payloads, and VIN frames automatically. It is my way of keeping the conversation with the car readable, whether I’m validating my own adapter firmware or reverse‑engineering a random aftermarket device.

Powered by CornucopiaStreams

The other half of the story is CornucopiaStreams, my transport abstraction that grew out of those same diagnostic sessions. After testing dozens of adapters I wanted one code path for every physical link. CornucopiaStreams is that “horn of plenty”: point it at a tty://, tcp://, ble://, ea://, or rfcomm:// URL and it hands back a matched Input/OutputStream pair. Serial over USB, Wi‑Fi bridges, BLE UARTs, even MFi External Accessories all look identical to ELMterm. That means I can swap transport layers in seconds—one moment I am on a USB cable in the lab, the next I am walking around the car with a BLE prototype—without changing a line of REPL logic.

Where to get ELMterm

ELMterm lives on GitHub under the Automotive‑Swift org:

- Repository: https://github.com/Automotive-Swift/ELMterm

- License: MIT

- Requirements: Swift 6.2+, macOS 13+, Xcode command line tools.

Clone it and build the release target:

git clone https://github.com/Automotive-Swift/ELMterm.git

cd ELMterm

swift build -c release

The binary will appear at .build/release/ELMterm. Because it is a SwiftPM project you can also swift run ELMterm … while iterating.

How I use it day to day

Pick any adapter URL that CornucopiaStreams understands and pass it to ELMterm:

# USB serial, common bitrate

tty_url="tty://adapter:115200/dev/cu.usbserial-ELM"

ELMterm "$tty_url"

# Wi‑Fi bridge

tcp_url="tcp://192.168.0.10:35000"

ELMterm "$tcp_url"

# BLE prototype (service FFF0)

ble_url="ble://FFF0"

ELMterm "$ble_url"

Once connected you get a readline‑style prompt (configurable via --prompt) with command history that persists to ~/.elmterm.history by default. I tend to keep timestamps on (--timestamps) when validating long bench sessions, and the new theming support lets me switch between a light palette (perfect for my yellow terminal) and a dark palette for late‑night hacking (--theme light|dark).

A few other flags I reach for:

- --terminator crlf to match adapters that expect both CR and LF.

- --hexdump when I suspect malformed frames and want ASCII + hex simultaneously.

- --plain to disable annotations when I am profiling raw throughput.

- --config ~/.elmterm.json so field gear inherits the same defaults without more CLI typing.

Inside the REPL there are helper commands (:history, :clear, :analyzer on|off, :save, :quit) so I rarely leave the keyboard while probing.

What’s next?

ELMterm and CornucopiaStreams continue to evolve together. Every time I touch a new transport—say, BLE L2CAP with a custom ECU, or a TCP bridge baked into a logger—I add the capability to CornucopiaStreams and immediately reap the benefit in ELMterm. Likewise, improvements in the analyzer (better ISO‑TP handling, rich metadata, smarter VIN extraction) go straight into my daily workflow. Building my own adapter removed the “can I trust the hardware?” anxiety; building ELMterm removes the “can I trust my tooling?” anxiety.

If you work on OBD‑II/UDS diagnostics, or you simply want a terminal that actually understands what your automotive adapter is telling you, give ELMterm a try. Clone it, point it at your favorite transport, and let CornucopiaStreams do the heavy lifting while the REPL keeps you in the loop. Happy hacking, and see you on the CAN bus.

RetroPlayer – Bringing the Sound of My Youth to iOS

Some projects aren't just about building software—they're about preserving memories, honoring the past, and sharing what shaped you. RetroPlayer is one of those projects for me.

Growing up in the 1980s, I spent countless hours in front of a Commodore 64, and later an Amiga, absolutely mesmerized by what these machines could do. The graphics were captivating, the games were endlessly replayable, but what truly captured my imagination was the sound. The SID chip in the C64—with its distinctive three voices—could produce music that seemed impossible for such simple hardware. Composers like Martin Galway, Rob Hubbard, and Ben Daglish weren't just writing game soundtracks; they were pushing silicon to its absolute limits, coaxing basslines and melodies from chips that were never meant to be musical instruments.

The Amiga took this even further. Paula's four-channel PCM audio opened up a whole new world of sample-based music. The demoscene exploded, and suddenly you had MOD files—tracker music that felt like the future. Each machine had its own sonic fingerprint, its own limitations that somehow became strengths in the hands of talented composers.

Full Circle

Fast forward to 2008. The iPhone SDK had just been released, and I was itching to build something meaningful for this revolutionary new platform. What did I choose? A SID player. My very first iOS app was dedicated to playing those legendary Commodore 64 tunes that had been the soundtrack to my childhood. It felt right—bringing the sounds that defined my youth to this cutting-edge device in my pocket.

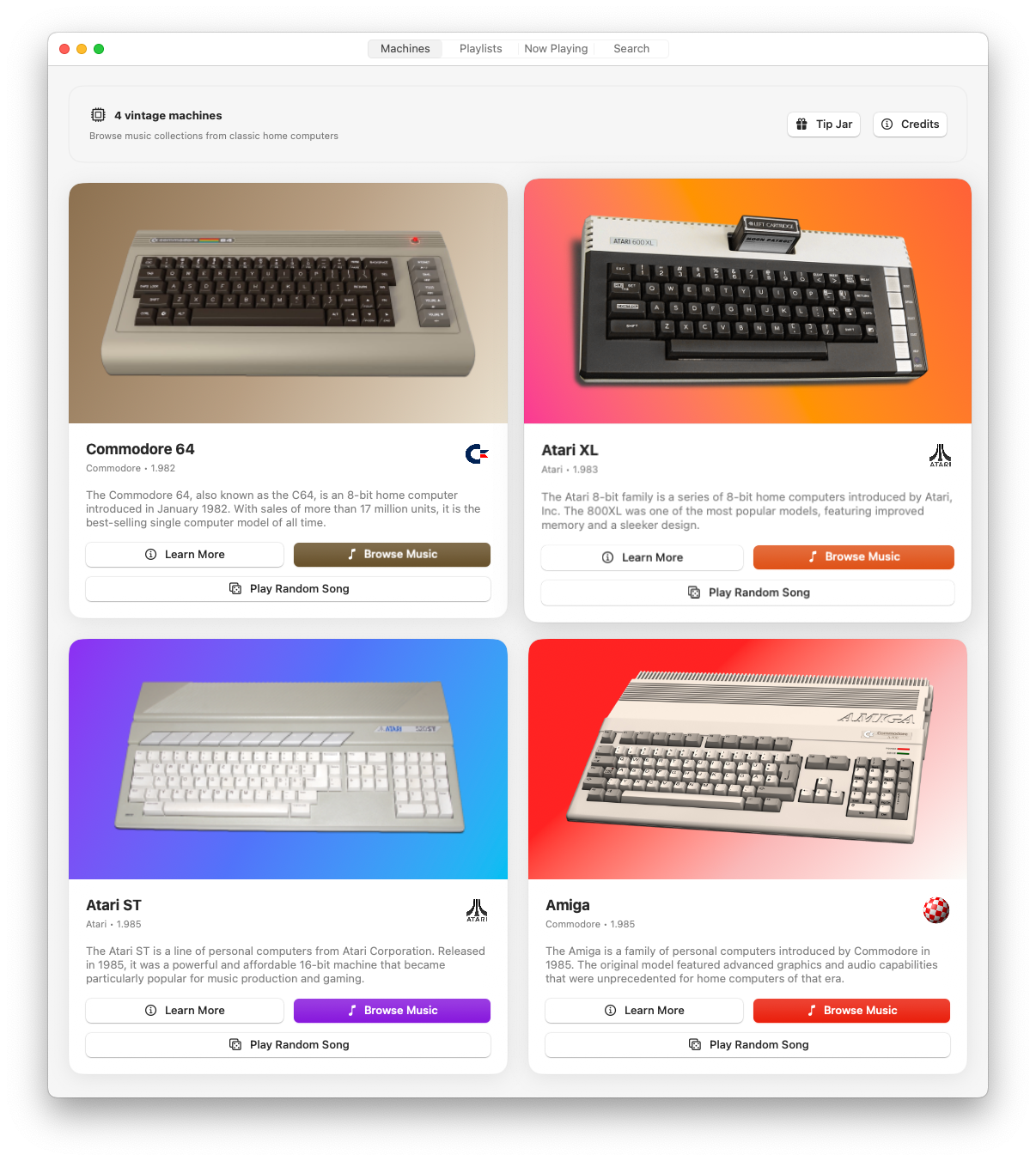

Now, seventeen years later, I've come full circle with RetroPlayer. But this time, it's not just the C64. RetroPlayer brings together the iconic sound chips from all the machines that defined that golden era: the Commodore 64's SID, the Amiga's Paula, the Atari XL's POKEY, and the Atari ST's Yamaha YM2149.

What RetroPlayer Does

RetroPlayer is a love letter to classic computer music. It's built natively for iOS, macOS, and even visionOS, using modern SwiftUI while paying homage to the aesthetics of those vintage machines. Each platform has its own visual identity—period-authentic imagery and brand gradients that evoke the original hardware.

The app taps into the incredible work of preservation communities like HVSC (High Voltage SID Collection), ASMA (Atari SAP Music Archive), SC68, and MODLAND, giving you access to thousands of authentic chiptunes. You can browse curated playlists like the HVSC Top 100—the most beloved C64 tracks of all time—or dive into the complete works of legendary composers.

But my favorite feature? The real-time oscilloscope visualization. Watch the audio waveforms dance across your screen with phosphor-trail effects that evoke vintage CRT monitors. It's both a visual treat and a window into the raw audio synthesis happening beneath the surface—the same waveforms that fascinated me as a kid, now rendered in real time on modern hardware.

A Modern SID Player for macOS

While RetroPlayer works beautifully on iOS, iPadOS, and visionOS, I also built a full-featured macOS desktop version. If you've been following the SID player scene on Mac, you might know that SIDPLAY hasn't been updated since 2016. RetroPlayer fills that gap with a native Apple Silicon app that brings the same curated playlists, real-time visualization, and extensive music catalog to your Mac.

Why This Matters

There's something profound about hearing these sounds again. It's not nostalgia for nostalgia's sake—it's about recognizing the creativity, the ingenuity, the sheer artistry of composers who worked within severe constraints and produced timeless music. These weren't just bleeps and bloops; these were compositions that inspired generations of electronic musicians.

RetroPlayer includes full playback features: background audio, system media controls, lock screen metadata, favorites management, and powerful search across the entire catalog. It even supports CarPlay, so you can take Wizball, Last Ninja, or Sanxion with you on the road.

The Journey Continues

Building RetroPlayer has been deeply personal. From that first SID player in 2008 to this comprehensive multiplatform app in 2025, it's been a journey of growth—not just as a developer, but as someone who wants to preserve and share the sounds that shaped him.

For those who grew up with these machines, RetroPlayer is a way to revisit those sounds authentically. For newcomers discovering chiptune music for the first time, it's a gateway to understanding why these simple sound chips captivated an entire generation.

The C64 and Amiga taught me that limitations breed creativity, that constraints can inspire brilliance, and that sometimes the most memorable art comes from pushing technology beyond what it was meant to do. RetroPlayer is my way of keeping that spirit alive—one authentic waveform at a time.

If you want to experience the sound chips that defined a generation, RetroPlayer is waiting for you on the App Store. And if you've never heard the punchy bass of a SID chip classic or the sample-based richness of an Amiga MOD track, well… you're in for a treat.

Stay curious, and keep the old sounds alive.

Do old‑style version numbers still make sense?

Long before the endless scroll of release notes and automatic updates, software came packaged in physical media: floppies, CDs, DVDs. Version numbers were lovingly crafted—Version 3.5.2 meant something. It signaled a meaningful hierarchy: major features, minor improvements, bug fixes. You’d carefully note it in a spreadsheet, or stamp it on the media sleeve, and you knew exactly what you had.

Back then, if you were shipping a desktop app on CD, you couldn’t just push a micro‑patch. You needed a build, a test cycle, a labeled release. A three‑part version number made sense: major.minor.patch told a coherent story.

Then came broadband, app stores, Docker containers, continuous deployment pipelines—and everything changed. Today, software updates roll out automatically, sometimes multiple times per day. Does 3.5.2 still mean much in a sea of nightly builds and daily hot‑fixes?

Let's compare the old and new world:

Hand‑crafted version numbers (e.g. 2.4.7)

Pros:

- Convey structured meaning: major changes vs bug fixes.

- Easy to reference in support, documentation, or bug reports.

- Feels final, stable, versioned. Good for releases on solid media.

Cons:

- Arbitrariness in deciding what merits a version bump.

- Bottleneck: a human must decide to increment.

- Misleading in fast‑update contexts: “Oh, version 2.4.8? Is it worth updating today?”

Date‑based version numbers (e.g. 2025.06.20)

Pros:

- Clear timestamp: exactly when it was released.

- Scales effortlessly: daily, hourly, on‑the‑fly.

- Avoids ambiguity over “minor” vs “patch”—every build is traceable.

Cons:

- No structural hierarchy: can’t tell at a glance if it’s a major feature or a tiny fix.

- Slightly more verbose.

- Feels less “semantic” — you can’t infer scope from the version itself.

A possible compromise

What if we combine both? Let me propose a concatenation of major version and date, e.g. 5 – 2025.06.20.

Pros:

- MajorVersion indicates broad, breaking, feature‑set changes.

- Date signals exactly when you shipped it.

- Updates during the same day can have additional prefixes, if necessary.

- A major bump (say, 6 – ...) only happens on real, feature‑heavy releases.

Cons:

- Slightly more verbose.

Why this hybrid works? Because clarity meets structure. You immediately know: “Yep, still version 5, same major features as earlier builds, but built on June 20, 2025.” It’s also flexible: Keep shipping bug fixes or minor features even daily—no need to agonize over whether it’s 5.0.1 or 5.1.0. Last but not least, it because old‑school meets modern. You have the stability sense from “version 5” and the transparency of “built on 2025‑06‑20.”

Conclusion

We’ve evolved from floppy‑based releases where version numbers were carefully picked, to a sprawling world of ubiquitous, atomic updates. In that old era, structured numbering made sense; today, time‑stamps are king. But we don’t have to choose—by adopting a major‑version + build‑date scheme, we bridge both worlds.

Whether you distribute on physical media or via container orchestrators, you get:

- Semantic hierarchy, from major version.

- Precise timing, from date-based builds.

- Simplicity, avoiding patch/minor version anxiety.

In a world where software never really ends, maybe it’s time we let version numbers reflect what changed and when – without overthinking the how many dots. Stay curious, version wisely, and happy shipping.

Back to C++

I learned C++ in the late 1990s, back then with Microsoft's Visual Studio C++ and the Microsoft Foundation Classes. When I left Windows behind and embraced Linux and macOS, I concentrated on Objective-C, Vala, and (since 2020, being late to the game) Swift.

Just recently I started getting into MCU programming (notably the ESP32-series). As I'm (still) not very fond of C, I was pleasantly surprised to see that C++ was supported well. I didn't look at C++ for almost two decades, but I like what the committee did since 2014. Type inference, move semantics, coroutines, ranges, and all that are pretty helpful and can help secure the usability of C++ in an almost saturated world of programming languages.

Naturally I started with abstractions, this time for FreeRTOS “objects”. FreeRTOS is a simple, yet pretty capable operating system and it provides most of what you will need to write concurrent programs. Although – after stumbling about the most impressive Swift for Arduino – I had wished I could write in Swift, C++ is really fine these days. I have a nice development environment with a capable language now.

Stay tuned for a more detailed progress report of what I'm actually building.

Activating an Apple Watch eSIM w/ O2

When activating an Apple Watch eSIM, the process is usually pretty straightforward. Most providers are using a QR code that you can scan during setup – this transfers the eSIM data and off you go. Not with O2 though – at least here in Germany; they open a builtin web browser and require you to log into your account to order the eSIM from within your account.

So I tried this. During eSIM setup in the O2 login form, you can choose between login via E-Mail-Address or phone number. If you try the E-Mail-Address you get an error message w/ “Please register with the O2 App”. If you use the phone number here, you'll get a prompt “This device's phone number does not belong to your account. Please use a different account”. And now you're stuck.

So after investigating several ways (the O2 support not being helpful at all…), I found the culprit: When you have multiple tarrifs in your account, the automated process does not scan all your phone numbers, but only takes the first one, the “main phone number”. What you now have to do is to login (best via web portal) and change the main phone number to the one you want to order an eSIM for (you can change it back again after the process).

Once you did that, you can finally use that phone number to login during the eSIM setup process and ordering should work.

SPM-ifying YapDatabase

Converting an existing Objective-C/Swift framework to Swift Package Manager

I'm a big fan of the database library YapDatabase, which is a collection/key/value store for macOS, iOS, tvOS & watchOS. It comes with many high level features and is built atop sqlite.

In the last 5 years, I have used this successfully for many of my projects. It is written in Objective-C and comes with a bunch of Swift files for more Swifty use. Since I recently announced to go all-in with Swift, I want to convert all my dependencies to the Swift Package Management system. I have never been a fan of CocoaPods or Carthage as I found them too invasive.

As this point of time though, YapDatabase is not Swift Package Manager (SPM) compatible and all approaches to do this using the current source layout did fail. So I had a fresh look at it and decided to do it slightly differently: If you don't have to work with the constraints of an existing tree layout, the process is relatively straightforward. Read on to find out what I did.

Prerequisites

- Use swift package init to create a package named YapDatabase.

- Edit Package.swift to make the package create two libraries with associated targets

- ObjCYapDatabase is going to hold the Objective-C part in Sources/ObjCYapDatabase,

- SwiftYapDatabase is going to hold the Swift parts in Sources/SwiftYapDatabase.

I couldn't name the Objective-C library simply YapDatabase, since this would have required to rename the (then umbrella) header file YapDatabase.h, which I didn't want to.

Swift vs. Objective-C

At the moment, SPM is not capable of handling mixed language targets, i.e., you either have only Swift files or no Swift files at all in your target – therefore I split the repository accordingly and moved Swift files below Sources/SwiftYapDatabase.

Source and Header file locations

SPM is pretty rigid when it comes to the location of source and header files. This is the reason why I unfortunately could not deliver this work on top of the original source repository.

Fortunately though, the source repository was very well structured. To layout the files in a way that makes SPM happy, I

- Created two header file directory, include for public headers, privateInclude for private headers.

- Moved all header files from Internal directories and those with private in their name to the privateInclude directory.

- Moved the remaining header files to the public include directory.

Swift

The aforementioned steps were enough to make SPM compile the ObjCYapDatabase. To make the Swift part compile, I had to

- Edit all Swift files to import ObjCYapDatabase instead of Foundation via sed -i -e s,Foundation,ObjCYapDatabase,g *.swift.

This made the SwiftYapDatabase compile.

What's Next

There are some parts missing: I didn't include the example programs, the tests, and the Xcode project.

I don't know Robbie Hanson's (creator of YapDatabase) plans. As it stands, this shuffling around was merely a proof-of-concept to find out whether such an approach is sufficient to SPM-ify YapDatabase or whether to there are more problems to consider. I will incorporate this in one of my projects to put it through a real world test.

I have published the repository as SwiftYapDatabase and will report this work via the YapDatabase issue tracker. Let's see what happens next.

Programming Languages

While I never got much into natural languages (beyond my native tounge, a halfway solid english, and some bits and pieces of french), I have always been fascinated by (some) programming languages – I even wrote books about some of them.

I (literally) grew up with BASIC and 6502/6510 ASSEMBLER – on the VC20 and the C64. Later on, learned to hate C and love 680x0 ASSEMBLER – on the AMIGA. During the 90s, I enjoyed PASCAL and MODULA II, and then found a preliminary home in Python.

The 2000s were largely affected by C++ (which I always found much more interesting than JAVA) until I got acquainted with Objective-C – which later rised to the 2nd place in my top list – shared with Vala, which I still have a sweet spot for, since it liberated me from having to use C.

As I grew older (and suddenly realized that my lifetime is actually limited, imagine my surprise…), I learned to embrace higher abstractions and being able to formulate algorithms clear and concise. While Python allowed me to do that, its reliance on runtime errors as opposed to compile-time always bugged me.

During the 2010s, I settled on using Python on the server, and Objective-C on the client – still dreaming about a language I could use for both.

Fast-forward to 2020.

I have been a vocal critic of Apple's new language, Swift, since its debut – for reasons which I'm not going to repeat. Three months have passed since I started learning Swift and I think it's time for a first preliminary report.

TLDR: I like it – a lot more than I have ever thought – and will from now on try to use it pretty much everywhere.

Before moving on with some details, let me also confess that I'm pretty glad having waited for so long. Judging from the outside, the road to Swift 5 was a very rocky ride. Were I to begin with an earlier version, I might have given up or wasted many hours following a language that was such a moving target – changing every year in more ways than I would have been willing to participate.

Syntax, Semantics, and Idioms

Swift is very expressive and rich in syntax, semantics, and idioms – and it has a tough learning curve. As someone who has written Objective-C for almost a decade now, let me tell you that whoever told you that Swift is more accessible than Objective-C is a downright lier. Objective-C is a very simple language, as it adds one (yes, just one) construct (and some decorators) on top of another simple language – C.

Once I was beyond my reluctance to look into it, I finally see the beauty. Swift has almost everything I have ever wanted in a programming language. Among many other features, it has

- type safety,

- generics,

- multiple inheritance (in the disguise of protocols with default implementation),

- closures,

- type inference,

- namespaces (ok, not first class, but think enums without cases),

- rich enums,

- …

On top of that it has a REPL (Read-Eval-Print-Loop), which can't be praised enough – it is the #1 missing feature in most compiled languages – and syntax for building DSLs (Domain Specific Languages).

And: It is Open Source – which is the #1 feature that has always irritated me with Objective-C.

Interoperability

I hate repeating myself. I love generic solutions. Over the last decade, I created a number of reusable frameworks that powered all the apps I wrote. It has accumulated quite a bit of stuff, as you can see here (generated using David A Wheeler's SLOCCount):

SLOC Directory SLOC-by-Language (Sorted)

2110719 LTSupportCore objc=2063905,ansic=31423,java=5914,cs=3822,cpp=2772,

106939 LTSupportDB objc=106108,sh=831

35669 LTSupportTracking objc=17443,ansic=12219,cpp=4922,java=902,sh=128,

30331 LTSupportUI objc=30053,sh=278

27116 LTSupportDRM objc=27116

9499 LTSupportBluetooth objc=9365,python=134

6143 LTSupportAutomotive objc=6143

5141 LTSupportAudio objc=5141

4510 LTSupportVideo objc=4510

3324 LTSupportCommonControls objc=3324

679 LTSupportDBUI objc=679

340 LTSupportMidi objc=340

271 LTSupportDiagnostics objc=271

One of the things contributing to scare me before switching to Swift was that I may had to rewrite all that again. But it ain't necessarily so.

Calling Objective-C from Swift

Being probably the company that has the largest Objective-C codebase in the world, Apple worked hard on interoperability. Calling Objective-C from Swift is a breeze – they'll even convert method names for you. Not much to complain here. Almost every Objective-C construct is visible to Swift.

Calling Swift from Objective-C

Calling Swift from Objective-C is a tad bit harder. Apart from having to including (generated) extra headers, the whole plane of types with value semantics is more or less invisible to Objective-C. There are ways to bridge (AnyObject), but it's cumbersome and sometimes very for generic code (__SwiftValue__).

Beyond Apple

In a surprising move, Apple released Swift as an open source project. And although the struggle of combining a product oriented software release cycle with a community oriented evolution process is sometimes obvious (you can follow the tension if you read some of the evolution threads on the Swift forums), they manage it quite well.

What catched my attention in particular was the invention of Server-side Swift and the Swift Package Manager, since these two projects have the power to replace my use of Python forever.

Foreign Platforms

My new set of swift-frameworks will be open source and also support UNIX-like platforms (to a certain degree, since Apple still has their crown jewels like UIKit and AppKit closed), hence finally I can use my reusable solutions both on the client and the server.

Unfortunately Google backed somewhat out of using Swift. For quite some time it looked like they would embrace it as another first-class language for their forthcoming Android successor. This would have been the icing on the cake, but let's see – Kotlin is pretty similar Swift, but not it.

Conclusion

I'm now familiar enough with Swift that I made the decision to go all-in, helping to improve the server-side ecosystem as I go. Speaking about which – I still miss a bunch of features, in particular first-class coroutines for asynchronous algorithms, a proper database abstraction, and a cross-platform logging solution. But what I enjoy the most is to be a part of a vibrant (language) community again. People are way more excited when it comes to Swift as they ever were with Objective-C. And this is great!

Feeling like Don Quixote

For some years now, I have been feeling like Don Quixote fighting against windmills. This is a multidimensional feeling that has its roots in both personal and professional circumstances. With regards to personal issues, I won't go into details as I want to keep this blog free from politics, society, and economics.

With regards to professional circumstances, something that bugs me a lot is that I seem to engage in fighting wars that can't be won. Free software lost a lot of wars, most notably though in the mobile sector. As I have complained more than once before, over the last decade, the phone and tablet world has become much less free. Even big companies struggle these days and it looks like we're stuck with a duopoly for a long long time.

Today though I want to complain about one of these two players, namely the Apple development platforms. By 2013, software development for Apple devices was a lot of fun. We had a great mature language, nice frameworks, and a big market to try out all kinds of ideas and ways to make a living. For some reason though this changed, when Apple introduced the Swift programming language. It split the developer world and alienated a lot of the veterans.

The claims of better readability, performance, and what not could not be achieved. In fact, I (and a lot of people not wearing rose-colored glasses agree with me) think, what has been proposed as a way to flatten the learning curve is actually harder to learn and less readable.

For the major part of the last years I ignored everything Swift, hoping that for the remainder of my professional career (lets say 20 more years, if all goes well) Objective-C would be at least well enough supported that I could continue writing programs -- even without a vibrant open source community (since most folks have switched to Swift immediately and despite popular belief mix and match is not a thing) and proper API docs.

Last year though the first swift-only frameworks and a whole new approach for semi-declarative UIs appeared. SwiftUI -- they even named it like the programming language sigh. This year they are “moving forward” by deprecating more Objective-C frameworks and introducing SwiftUI as the one and only way in some places.

It's now clear to me: It's either I leave the platform or I stop trying to achieve perfection with a certain -- restricted -- set of tools but rather walking their rocky road. And I must confess, I still love the Apple platform so much that I give up fighting aginst the windmills and start from scratch. Learning SwiftUI. Learning Swift.

On a slightly related note: For a new contract, I have to revisit the successful build system I co-founded 20 years ago: OpenEmbedded. Though being quite rusty (left the project 11 years ago), I'm looking forward to finding out what the community made out of it.

Stay safe and healthy.

Welcome, 2020

Here's the new decade. 2019 went by as an important year where I regained some of my health, discipline, and motivation.

Next to the inevitable iOS development, the most important milestones were the release of the 2nd edition of my Vala book and my first music album after more than two decades of inactiveness.

I'm looking forward to this decade. The best is yet to come.

Fabrique Noir – Space Travel

I'm enjoying creating music since 1981. First on analogue synthesizers (SIEL OPERA 6) and drum machines (ROLAND TR-505), later on with digital synths and workstations (KORG M1, KORG 01/Wfd). From 1986 to 1989 I created my music mainly on the COMMODORE AMIGA. The PC platform almost killed my motivation. Switching from hardware sequencers to a software sequencer was tough for me, later on an abundance of possibilities (I earned money and bought too many devices) somewhat paralyzed me. The birth of my daughter Lara-Marie in 2011 did add a share to my “uncreative pause”.

Still, I never stopped enjoying (making) music, in the meantime with Pianos, Guitars, and Ukuleles. Over three decades worth of melody and text fragments have continued to haunt me again and again (“use us, finish us, ...”).

When I had health issues early this year (everything well now), I finally vowed to my self to start releasing music again. Four months later the first result of these endeavours can be seen. Originally it should've been a completely different thing, but sometimes creative processes take their own turns.

My first album after three decades of mostly idling is called “Space Travel”, inspired by the legendary Apollo 11 mission from 1969. It is an electronic album and available here:

As for the aforementioned melody and text fragments… apart from one tiny sequence, there is only new material on this album. I wanted to check whether I still have the mojo before going back in time. A bit of more info with regards to the tracks is here.